I baked my first Appalachian Apple Stack Cake last week to celebrate my parents’ birthdays. They were born on the same day in November two years apart.

The cake-making turned into a multi-day affair—procuring apples, sorghum and apple butter at Mercier Orchards and then baking two layers of cake in three batches to make six layers. The layers needed to soften into the fruit spread in the fridge overnight.

By the time we ate it, Mom was in her feels about the cake and family and time. (I’m an emotional person too and love a recipe with a big past, so I get it.) She passed Dad a slice with some fanfare by telling him that the cake represents layers of stories and good times. He muttered something like, “Well, they weren’t all good times.” Dad keeps it real.

But these cakes do seem to pack in a lot of story. “No dish is so emblematic of the mountain South as apple stack cake,” writes Ronni Lundy in her masterpiece of a book, Victuals. “Its ingredients are modest, but when its parts are assembled, it stands tall and proud.”

She also says it requires patience (I agree), and she says it might be based on the layered tortes of Eastern Europe brought to the region by early German immigrants. The Appalachian version is more rustic and made with ingredients familiar to mountain folks.

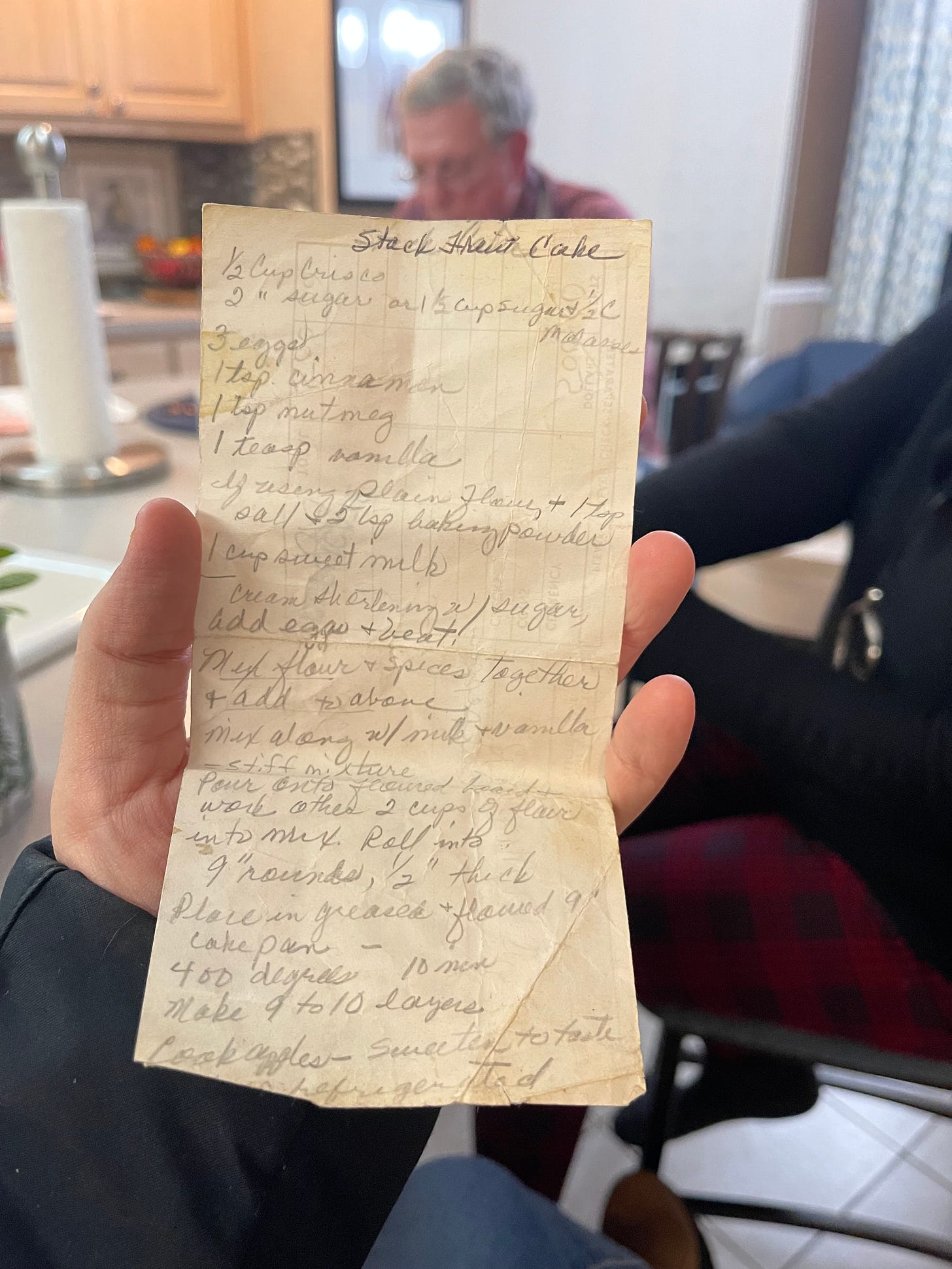

I found two recipes for the cake in Mom’s recipe box including this one written on the back of a bank deposit slip from 1983.

Mom doesn’t remember who gave her the recipe. But it did remind me of a story I wrote a while ago about a robbery at this bank’s branch in our little mountain town.

Cake is involved. Sort of.

Robbing Banks, Mining for Gold

I grew up straddling a state line where tiny twin communities—McCaysville, Georgia, and Copperhill, Tennessee—come together. It’s where they claim a bride at the Catholic church can start down the aisle in Georgia, but at the altar, she’s in Tennessee. At least one man served as mayor of both towns in separate terms without having to move residences. He said he ate breakfast in one state and brushed his teeth in the other.

The state line does not follow the river that runs through the towns. So growing up, I never understood exactly where it fell. But on a return visit, I noticed something new— a bright blue stripe cutting through the parking lot of the IGA Grocery. It parted a Toyota 4Runner and a Ford F150 like Moses parting the sea. “There it is!” I shrieked, and we pulled over so I could snap a photo.

Later that day, I showed the photo to Mom. She wasn’t impressed.

“Who knows if it’s accurate,” she smirked, taking a quick glance and then turning back to the dishes.

Her indifference sort of shocked me. Many of us who’ve lived on the line relish the whimsey of the experience, and Mom has been a proud line-straddling resident most her life.

“What do you mean?” I asked her.

“Well, I had a hand in getting it painted,” she said, which was news to me. “We weren’t really sure.” And then she added in a whisper, “But nobody else knows either.”

Turns out, the blue line — and some other proclamations of its whereabouts — might have been educated guesses for the sake of business or tourists. Legend has it the surveyors back in the day were drunk when they visited and never made a clear record of the border. “There have been arguments about it for years,” Mom says.

But the peculiarities of my hometown hardly end at the line.

Back in 1843, prospectors hoping for gold found copper in the red clay hills. Copper mining until the mid 1980s along with logging and gases from smelting ore, cleared and scorched every sprig of vegetation for 50 square miles. Nestled into the lower corner of the Appalachian mountains, the area should have been covered in forested green. But when I grew up it looked as if a patch of Mars had been plopped among the soft, lush peaks.

Deep gullies eroded into the red clay leaving it stripped and routed. My brother and I called it “the dunes.” National Geographic even covered the environmental disaster, which could be seen from outer space. And in my Dad’s younger days, he says there were no fish in the lake and townspeople would ooh and ahh in the streets over the rare sighting of a bird. “Oh we coughed and wheezed all the time,” a friend of Mom’s recalled.

Because of this phenomenon, I never had to wonder about the color and texture of the earth where I come from. My terroir as the French call it —the set of environmental factors that affect a crop grown in a place—was stripped and starkly exposed. And exposed is how I felt when I left my small town too. Even at the University of Tennessee just a few hours north, my rural accent fell out of my mouth like a clanging cowbell.

Over the years, the accent mellowed a bit. The mining at home dried up, and the red clay eventually became threaded with kudzu and pines growing alongside the old mine shafts. But even with the red clay covered, I wonder what of my terroir remains with me now. These days, I search for—and crave—the peculiarities and the richness in the red clay I can’t find anywhere else.

While working as a food writer, I sometimes find it in the more unusual recipes of the region like chow chow, red bud jelly and apple stack cakes that used to sit in Tupperware on my grandmother’s washing machine as she told us stories around the kitchen table. I think I learned to love storytelling listening to her and other relatives, gathered with my aunts and uncles as they smoked cigarettes and drank black coffee.

Here’s one I picked up along the way.

About three decades ago, the bank in our one-stoplight town was robbed. At first, the teller —unaccustomed to such crime drama—thought the president of the bank was playing a prank.

“Mr. Rundles,” she said in a head-cocked, hip-out sort of way. “What are you doing wearing a ski mask?”

The robber responded by shooting a hole in the wall behind her. The other tellers hit the deck as the man barked orders. “If you need a hostage, take me!” shouted one woman, a customer. “I’m old!”

Meanwhile, Swannie Swanson of Swanson’s Jewelry Store next door heard the shot. He snatched a decorative antique revolver hanging from the wall, loaded it and rambled out the door waving it like a character in a Western movie. Another bystander, who escaped the bank building, bolted across Main Street to the competing bank across the way. In his panic, he bypassed the front door and rapped on the window of the president’s office. When the executive lifted the window, the man dove inside.

As the shenanigans carried on out front, the robber slipped out the back door with his cash. A bank employee hiding under her desk mustered the nerve to reach for her desk phone to call the freestanding drive-thru in the bank’s back parking lot.

“Do you see a man with a cape?” she whispered to her co-worker in the drive-thru. The robber for some reason wore a cape with his ski-mask. But her co-worker in the drive-thru didn’t pick up on any stress. She clonked down the receiver and wandered into the parking lot to take a look around.

“No, honey,” she said, when she returned. “There’s no man with a cake.”

“Cape!” the teller reiterated.

“No, I don’t see anyone with a cake.”

Looking back, I think about how I fled my hometown, in part, because I thought it was boring. We didn’t have a mall or manicured subdivisions like I’d seen on TV in the 80s. But I know better now. I see we had so much more in the peculiarities. It’s what I hope to keep mining in the red clay. And while I don’t need to rob any banks to find it, I’ll proudly be a lady in a cape with a cake who grew up on Mars.

Recipe:

I made this version of stack cake. I chose it for the brown sugar, butter and sorghum glaze, which I liked. But it did make the cake quite sweet and maybe less traditional than versions with just layers of cake and fruit.

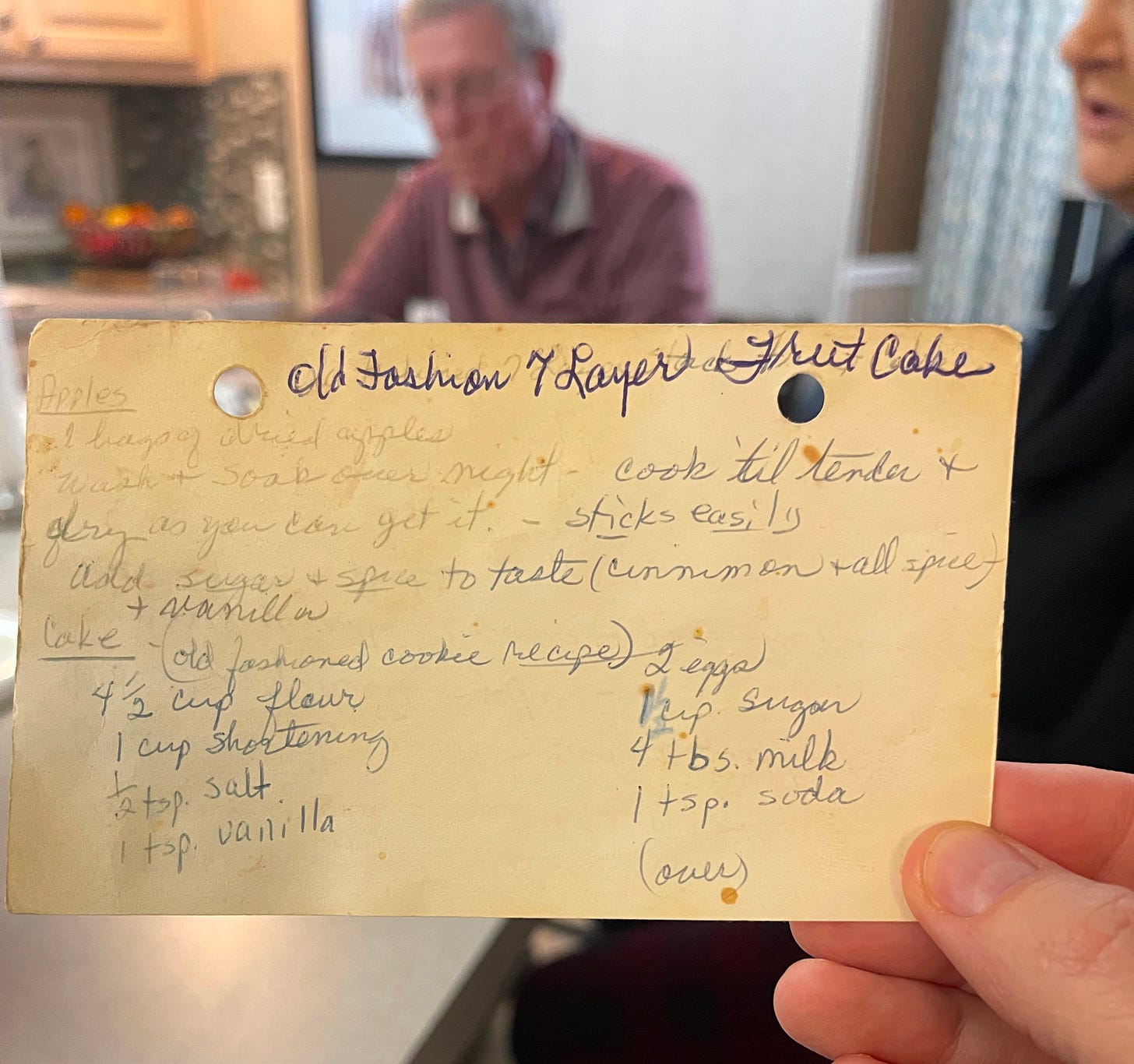

Here’s the second version I found in Mom’s recipe box. She has no recollection of where she got this one either. But she remembers her grandmother making these cakes, so we suspect it’s a version from her Mama King.

I’d also recommend Ronni Lundy’s version in Victuals, which comes from her Great-Aunt Rae.

If you’re new to these cakes, I want to note that the layers are really more like discs of cookie. The fruit mixture softens the layers, which means the cakes hit their peak state a couple days after baking.

Well, you've done it again.....left me in awe and appreciation of your gifted storytelling and a wonderful addition to the Keats family. Love, Linda